![Keon Sang-An Illustration by Denise Klitsie]()

From 1999 to 2009 I taught theology and missiology in the Horn of Africa, first in Asmara, Eritrea, and then in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.1 As a teacher in those contexts, I regularly observed students struggling with Western modes of biblical interpretation. They were often unfamiliar with and disinterested in abstract and rationalistic hermeneutical concepts and methodologies. Western hermeneutics did not offer helpful interpretive practices for these students, especially for the local churches they served. Furthermore, such sophisticated hermeneutical approaches led these students to ignore their own ways of reading the texts, neglecting practices that had been passed on in their historical and cultural contexts.

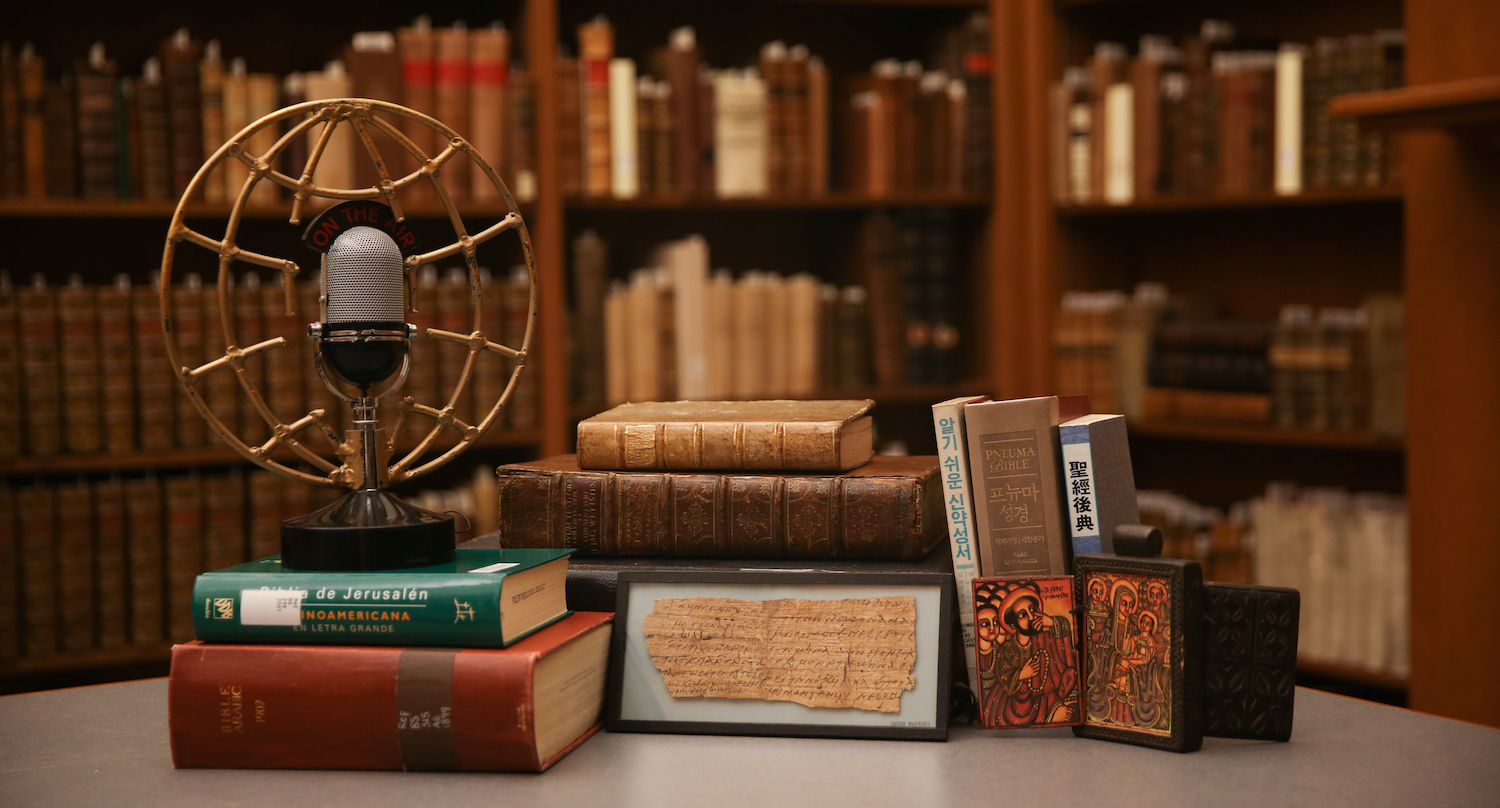

With this recognition, I began to encourage my students to understand the importance of constructing their own theologies in and for their historical and cultural contexts, rather than simply and passively accepting perspectives developed in different contexts. In particular, I worked diligently with my students in Addis Ababa to discover culturally relevant ways of reading the Bible in the Ethiopian context. Fortunately, there was a time-honored church tradition in Ethiopia: the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church (EOTC). It has developed and maintained its own ecclesiastical tradition in the Ethiopian context for almost as long as the history of the Christian church. Significantly, the EOTC has its own distinctive way of reading the Bible, which has been shaped and developed in the context of Ethiopia’s long history.

At that time, I had opportunities for fellowship with the teachers of the Theological College of the Holy Trinity, an Orthodox seminary in Addis Ababa. I visited the school and spoke with theology teachers there. They were happy about my interest in the EOTC and the theology of the church, and they graciously helped me in my research on the history and practices of interpretation in the EOTC. This interaction enriched and transformed my own theological perspective, especially in the area of biblical interpretation. I came to affirm the contextual nature of biblical interpretation and the significance of tradition and context.

THE CONTEXTUAL NATURE OF BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION

Biblical interpretation is inherently contextual. People in a particular context have a specific way of reading, hearing, and understanding biblical texts. In what follows, I will summarize several factors involved in the contextual nature of biblical interpretation.

Social Location

Fernando F. Segovia has noted two important and closely related developments in biblical criticism at the end of the 20th century. The first is the emerging recognition of the critical place of standpoint or perspective in biblical interpretation. The second is the increasing diversity of biblical interpretation that has derived from new perspectives and standpoints around the globe.2 I would argue that these interpretive developments are primarily concerned with the contextual nature of biblical interpretation.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the social location of the reader and its impact on the reading of texts. Consequently, social location has been privileged as a primary factor that determines people’s understanding of the biblical texts. As C. René Padilla asserts, “For each of us, the process of arriving at the meaning of Scripture is not only highly shaped by who we are as individuals but also by various social forces, patterns and ideals of our particular culture and our particular historical situation.”3 People’s social location provides the perspective from and in which they see and understand the biblical texts.

In this discussion, I am referring to social location inclusively, incorporating both the location of a society and an individual’s position in the society. Corporately, social location includes the overall sociocultural and historical context of a society. Individually, social location may include “personal history, gender, ethnicity, race, nationality, place of residence, education, occupation, political perspective, economic status, religious views or commitments, and so forth.”4 All of these factors shape communal and individual human identities and influence our interpretive practices.

This perspective on social location is important because it recognizes communal and individual dimensions as significant factors. As Michael Barram asserts, “Every interpretation comes from a ‘place’ to the extent that no interpreter can fully avoid the influence of [his or her social location]. . . . As we read the biblical text, therefore, what we see, hear, and value is inevitably colored by our own situations, experiences, characteristics, and presuppositions.”5

Segovia also emphasizes the role of flesh-and-blood readers and their social location in the reading and interpretation of the Bible. He argues, “All such readers are themselves regarded as variously positioned and engaged in their own respective social locations. Thus, different real readers use different strategies and models in different ways, at different times, and with different results (different readings and interpretations) in the light of their different and highly complex social locations.”6 In actuality, there is a multitude of voices reading and interpreting the Bible from different parts of the world.

![Mark Roberts (headshot)]() “For many years, I have made listening to Scripture one of my spiritual and academic disciplines. I find that when I listen to Scripture being read, I hear things I have missed through ordinary reading. During the last five years I worked on a commentary on Ephesians (now published in Zondervan’s Story of God series). In addition to spending countless hours reading the text of Ephesians with my eyes, I also listened to a recording of this letter at least one hundred times. As I did this, the language of Ephesians became alive in new ways. I heard words differently and discovered connections between passages that I had missed. Now, with my commentary finished, I still devote time each week to listening to the reading of Scripture. This is a central practice in my devotional life.”

“For many years, I have made listening to Scripture one of my spiritual and academic disciplines. I find that when I listen to Scripture being read, I hear things I have missed through ordinary reading. During the last five years I worked on a commentary on Ephesians (now published in Zondervan’s Story of God series). In addition to spending countless hours reading the text of Ephesians with my eyes, I also listened to a recording of this letter at least one hundred times. As I did this, the language of Ephesians became alive in new ways. I heard words differently and discovered connections between passages that I had missed. Now, with my commentary finished, I still devote time each week to listening to the reading of Scripture. This is a central practice in my devotional life.”

+ Mark D. Roberts is executive director of the Max De Pree Center for Leadership at Fuller Seminary. Subscribe to his e-devotional for leaders at depree.org.

Church as the Interpretive Community

Hearing and reading the Bible is an inherently communal event. As Justin S. Ukpong states, “The readings are mediated through a particular conceptual frame of reference derived from the worldview and the sociocultural context of a particular cultural community. This differs from community to community. It informs and shapes the exegetical methodology and the reading practice and acts as a grid for making meaning of the text.”7 Each and every culture has its own way of hearing or reading and understanding a text. Practically, in many cultures, reading or hearing the biblical texts is primarily performed in the context of community instead of by an isolated individual reader.

The faith community, in particular, fulfills the role of the hermeneutical community in the process of interpreting biblical texts. As Scott Swain appropriately notes, “Reading is a communal enterprise for the same reasons that Christianity is a communal enterprise.”8 God has charged the church to “obediently guard, discern, proclaim and interpret the word of God.”9 As God’s people, the church is the intended addressee of the Bible. First, the biblical texts were written and read in the context of the community of God’s people. As Joel B. Green notes, “The biblical materials have their genesis and formation within the community of God’s people. They speak most clearly and effectively from within and to communities of believers.”10

In addition, the Bible addresses the contemporary church. God speaks to the church through the biblical texts; the immediacy of the Bible is experienced by the community of faith. Therefore, interpretation of the Bible is, primarily, the task of the church. Green asserts, “The best interpreters are those actively engaged in communities of biblical interpretation. . . . No interpretive tool, no advanced training, can substitute for active participation in a community concerned with the reading and performance of Scripture.”11

Thus, the church is the primary context for biblical interpretation. Importantly, local churches all over the globe are the hermeneutical community, as these reflect ethnic and long-term theological traditions. They are located in particular historical and cultural contexts. Each faith community reads or hears and understands the biblical texts and generates practices in their particular contexts.

Local Interpretations for the Global Church

Thus far, I have come from different perspectives to a singular argument that every interpretation of the Bible is contextual. All biblical interpretation is carried out by faith communities located in particular contexts. We interpret the biblical texts from our particular locations.

Accordingly, there are many different readings of the biblical texts among peoples in the world. As William A. Dyrness notes, “Just as history has been replaced by histories, theology now has been replaced by theologies. Each group, from its own perspective, is reading the biblical text and finding its own place in the story of Scripture.”12 Thus, the task of contextual biblical interpretation involves exploring and describing different ways people read biblical texts in their particular historical and cultural contexts.

It is important to recognize that the contextual nature of biblical interpretation is not an obstacle. Rather, it is a valuable asset for the biblical interpretation of the Christian church. As Ukpong rightly points out, any given reading appropriates only “a certain aspect or certain aspects of a text.”13 No one way of reading the Bible can claim to appropriate the totality of understanding the biblical texts. A text has multiple aspects, dimensions, and perspectives, which no single reading can totally grasp. Therefore, “the more perspectival readings of a text we are aware of, the more dimensions of the text are disclosed to us, and the better we can appreciate it.”14

In this respect, each local interpretation of the Bible in its historical and cultural context can make a unique contribution to a more holistic understanding of the Bible for the church of God. Christians can learn from each other’s interpretation of God’s Word. We are being transformed by the Word of God, and we proclaim the Word of God to the world. In this way, we build up the body of Christ for the glory of God. I would argue that this is the way that the church hears or reads, understands, and practices the Bible. As Green asserts, if “the church is one, holy, apostolic, and catholic,” as in the traditional confession of the church, “there is only one church, global and historical,”15 with the local churches as its contextual manifestations. This ecclesial unity validates local interpretations for the global church.

THE EOTC’S READING OF ISAIAH 53:8

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church (EOTC)16 provides a compelling historical example of contextual reading of the Bible, which has been shaped and developed under the substantial influence of the EOTC’s tradition in the historical and cultural context of Ethiopia. The biblical interpretation of the EOTC is most practically revealed in the preaching of the EOTC. As an example, I will analyze a sermon on Isaiah 53:8 given by a priest of the EOTC in a local church. The sermon centered on Isaiah 53:8 but referred to other biblical passages, which is frequently true of sermons of the EOTC. I will give an abstract of the sermon—which was titled “Who can speak of his descendants?”—followed by a discussion of the major interpretive characteristics the sermon reveals.

Abstract

“Who can speak of his descendants?” (Isa 53:8) is a word of proclamation regarding Jesus Christ. In Isaiah 53, the prophet Isaiah prophesied about the Messiah, including his nature, emptiness, suffering, and death. In 2 Corinthians 8:9, Paul writes that Jesus’ sacrifice is all for our sake. After his resurrection, Jesus returned to his glory. Now he reigns in all his power and authority. Jesus Christ is not a man, nor a prophet, nor a mediator. John 1:1–3 declares that he was the Word, who was ![Keon Sang-An Illustration by Denise Klitsie (3)]() with God and was God. He was with God. He created the world. He was God. This Word dramatically became flesh. He became man through the Virgin Mary. The prophecy in Isaiah 7:14 was fulfilled in Matthew 1:21.

with God and was God. He was with God. He created the world. He was God. This Word dramatically became flesh. He became man through the Virgin Mary. The prophecy in Isaiah 7:14 was fulfilled in Matthew 1:21.

Isaiah 53 is also significant in the story of the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:26–38). He was the financial minister of Queen Candace of Ethiopia, who went to Jerusalem to worship God. On the way back to Ethiopia, he was reading Isaiah 53. Philip explained to him the meaning of the passage and he received Jesus Christ. He was then baptized. He was the very next person to be baptized after the baptism of Jesus’ disciples. Thus, Ethiopia was the first country to receive baptism and to read the Bible. Ethiopia took the first initiative to seek God. Later, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church became the Tewahido church and, therefore, the true church. In this way, Ethiopia laid the foundation for Christianity.

Major Characteristics

The preacher interprets the biblical passage as having two historical references: the first is Jesus Christ and the second is the event regarding the Ethiopian eunuch. The prophecy and fulfillment schema is employed as the key interpretive approach. In this way, the preacher highlights both the salvation of Jesus Christ and the historical significance of the EOTC.

This sermon reveals four major characteristics of biblical interpretation in the EOTC. First, it is Christ-centered. Second, it employs a prophecy and fulfillment schema. Third, it seeks to connect the biblical text with the Ethiopian context. Fourth, it places an emphasis on the practice of faith.

Christ-Centered Interpretation

Christ is the center in the preacher’s sermon, and the text is christologically interpreted. He states, “‘Who can speak of his descendants?’ This verse is the word which exclaims on Jesus Christ.” He continues, “This was delivered by the prophet Isaiah. He lived in 700 BC. However, he spoke about Jesus, his very nature, suffering, death, emptiness, and so on, in Isaiah 53.” Then the preacher seeks the specific implications of the text in the New Testament. He states, “‘Who can speak of his descendants?’ The story is about Jesus Christ. Paul, in 2 Corinthians 8:9, tells us that Jesus’ submissions are all for our sake. The rich Christ became poor for us. The Lord sat on a donkey. He was buried in a human tomb. In order to make us free, he received suffering which we were supposed to take. Then he returned to his glory. Now he is in all his power and authority.”

This preaching demonstrates the traditional view of the EOTC on Christ. For example, the preacher states, “He is not the one who many people assume him to be. He is not man. He is not prophet. He is not mediator. Then who is Jesus? In order to know him we need to listen to John’s teaching. According to John 1:1–3, he was the Word. He was in the beginning. He was with God. He created the world. He was God. This Word dramatically became flesh. He became man. So who is Jesus? Jesus was the Word. What happened to him? He became man. How did he become man? Through the Virgin Mary. This was prophesied by the prophet Isaiah. Glory be to his mighty name!” This demonstrates that the EOTC reflects the traditional teachings on Christ of the early church.

Prophecy and Fulfillment in Christ Schema

The preacher’s interpretation of the biblical text follows the traditional prophecy and fulfillment schema between the Old and New Testaments, wherein Old Testament prophecies are accomplished in the New Testament. He states, “Isaiah 7:14 says, ‘Therefore, the Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel.’ Matthew 1:21 says, ‘She will give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins.’ Isaiah said that ‘She will be with child and will give birth to a son.’ And the gospel writer said that she gave birth to a son, and named him Jesus. The prophecy was fulfilled.”

Seeking the Ethiopian Connection

In this sermon, the text is interpreted in light of a special Ethiopian connection. For the preacher, the verse refers to the circumstances of the Ethiopian eunuch. He asserts, “Especially, the verse ‘Who can speak of his descendants?’ talks about an Ethiopian person. This verse refers to a particular situation he was in. He was the Ethiopian eunuch. . . . Let me read you the verse which records this truth in the book of Acts 8:26–38. The Ethiopian eunuch, whose name was Barosh, was the head of finances as ordained by Candace, queen of Ethiopia. . . . The man was reading Isaiah 53. Then he was baptized by Philip.”

![Alexis Abernethy (headshot)]() “Reading or listening to Scripture reveals new dimensions of God’s character and his purposes and motivates me to live more fully according to his word. It is like a daily blood transfusion where the Holy Spirit renews and refreshes me.”

“Reading or listening to Scripture reveals new dimensions of God’s character and his purposes and motivates me to live more fully according to his word. It is like a daily blood transfusion where the Holy Spirit renews and refreshes me.”

+ Alexis D. Abernethy is professor of psychology at Fuller’s School of Psychology, with research interests that have focused on the intersection of spirituality and health.

The preacher then seeks the implications of this event for the contemporary Ethiopian context: “Jesus told his disciples to get baptized after his baptism. The Ethiopian eunuch was the very next one who was baptized after that . . . The Ethiopian Orthodox Church shared his baptism early before . . . Therefore, Ethiopia was the first country to receive the baptism. Ethiopia laid the foundation of Christianity. . . . This country still lives by faith and will stay forever and ever. Amen!”

The preacher continues, “He accepted Jesus Christ before the Apostle Paul came to Christ. He knew Jesus before the Roman Empire and Greece. Praise be to his holy name! Through this man Christianity came to Ethiopia. Then later the Ethiopian Orthodox Church became the true church and Tewahido church. This is the way our faith came. This is our religion. . . . I am telling you that Ethiopia became the first Bible-reading country. I am telling you that Ethiopia took the first initiative to seek God.”

Emphasis on the Practice of Faith

Throughout his sermon, the preacher is concerned with the faith and life of contemporary believers. He consistently repeats the phrase, “Who can speak of his descendants?” and applies it to contemporary Christians.

“This verse is the Word, which exclaims on Jesus Christ. Among the generations, God saved those who spoke of him. However, those who did not speak of him perished. Even today, those of us who speak of him will be saved, but those of us who do not speak of him will [perish]. Nevertheless, the will of God is to save all. May God help us to speak of him and be saved!”

He continues to advocate for the traditional Christology of the EOTC, while bringing this Christology into the contemporary context. He states, “Today many believe that Jesus is man, prophet, and intercessor. They do not know him yet. They seem to worship him but they are not with him.” He repeats

this affirmation and adds an exhortation for his own generation: “Today many people say that Jesus is prophet, man, and mediator as the Pharisees say. We know Jesus by his teaching, not by the teaching of Pharisees. He is God the Creator. We do not doubt him as Philip did. We believe in Jesus as written in the Bible, not by assumption. . . . As the disciples were with Jesus, they did not know him. It obviously happens today in our generation. May God give a chance of repentance for those who went away from his presence!”

The central message of this sermon is the person and salvific work of Jesus Christ. The preacher employs a christological interpretation of the Old Testament text in Isaiah. The preacher also interprets the text as having another historical reference: the event regarding the Ethiopian eunuch. The preacher in this sermon seeks to highlight the salvation of Jesus Christ as well as the historical significance of the EOTC.

CONCLUSION

This particular sermon demonstrates the significant influence of tradition and context in biblical interpretation. The EOTC provides a compelling historical example of biblical understanding that has been shaped under the substantial influence of the EOTC’s tradition in the historical and cultural context of Ethiopia. Just as significantly, it helps to enrich our own understanding of God’s truth in the Bible.

ENDNOTES

1. This article is an extract from my book, An Ethiopian Reading of the Bible: Biblical Interpretation of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2005).

2. Fernando F. Segovia, “Culture Studies and Contemporary Biblical Criticism: Ideological Criticism as Mode of Discourse,” in Reading from This Place, vol. 2: Social Location and Biblical Interpretation in Global Perspective, ed. Fernando F. Segovia and Mary Ann Tolbert (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995), ix.

3. C. René Padilla, “The Interpreted Word: Reflections on Contextual Hermeneutics,” Themelios 7 (1981): 18.

4. Michael Barram, “The Bible, Mission, and Social Location: Toward a Missional Hermeneutic,” Interpretation 43 (2007): 44.

5. Ibid.

6. Segovia, “Culture Studies and Contemporary Biblical Criticism,” 7.

7. Justin S. Ukpong, “What is Contextualization?” Neue Zeitschrift für Missionswissenschaft 43 (1987): 27.

8. Scott Swain, “A Ruled Reading Reformed: The Role of the Church’s Confession in Biblical Interpretation,” International Journal of Systematic Theology 14 (2012): 180.

9. Ibid., 182.

10. Joel B. Green, Seized by Truth: Reading the Bible as Scripture (Nashville: Abingdon, 2007), 66.

11. Ibid., 66–67.

12. William A. Dyrness, The Earth Is God’s: A Theology of American Culture (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1997), 8–9. 13. Justin S. Ukpong, “Inculturation Hermeneutics: An African Approach to Biblical Interpretation,” in The Bible in a World Context, ed. Walter Dietrich and Ulrich Luz (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 26.

14. Ibid.

15. Joel B. Green, Practicing Theological Interpretation: Engaging Biblical Texts for Faith and Formation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011), 16.

16. The word tewahido in Ge’ez means “being made one” or “unified.” Traditionally Oriental Orthodox churches, which rejected the Chalcedon formula, have been known as “monophysite,” which means “one nature.” However, the EOTC rejects the term in favor of “miaphysite,” since “mia” stands for a composite unity, unlike “mono,” standing for an elemental unity. This doctrinal confession of Christ is clearly expressed in the name of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church. See Aymro Wondmagegnehu and Joachim Motovu, eds., The Ethiopian Orthodox Church (Addis Ababa: The Ethiopian Orthodox Mission, 1970), 98.

The post The Contextual Nature of Biblical Interpretation: An Ethiopian Case appeared first on Fuller Studio.

For Jessica, curiosity about others’ stories is one of the key pieces in becoming conscious of one’s own context and thus free to reach across the divide to the “other.” She shares about how one of her closest friends, who is white, Christian, and identifies as queer, is very different from her yet one of her most trusted friends

For Jessica, curiosity about others’ stories is one of the key pieces in becoming conscious of one’s own context and thus free to reach across the divide to the “other.” She shares about how one of her closest friends, who is white, Christian, and identifies as queer, is very different from her yet one of her most trusted friends

“For many years, I have made listening to Scripture one of my spiritual and academic disciplines. I find that when I listen to Scripture being read, I hear things I have missed through ordinary reading. During the last five years I worked on a commentary on Ephesians (now published in Zondervan’s Story of God series). In addition to spending countless hours reading the text of Ephesians with my eyes, I also listened to a recording of this letter at least one hundred times. As I did this, the language of Ephesians became alive in new ways. I heard words differently and discovered connections between passages that I had missed. Now, with my commentary finished, I still devote time each week to listening to the reading of Scripture. This is a central practice in my devotional life.”

“For many years, I have made listening to Scripture one of my spiritual and academic disciplines. I find that when I listen to Scripture being read, I hear things I have missed through ordinary reading. During the last five years I worked on a commentary on Ephesians (now published in Zondervan’s Story of God series). In addition to spending countless hours reading the text of Ephesians with my eyes, I also listened to a recording of this letter at least one hundred times. As I did this, the language of Ephesians became alive in new ways. I heard words differently and discovered connections between passages that I had missed. Now, with my commentary finished, I still devote time each week to listening to the reading of Scripture. This is a central practice in my devotional life.” with God and was God. He was with God. He created the world. He was God. This Word dramatically became flesh. He became man through the Virgin Mary. The prophecy in Isaiah 7:14 was fulfilled in Matthew 1:21.

with God and was God. He was with God. He created the world. He was God. This Word dramatically became flesh. He became man through the Virgin Mary. The prophecy in Isaiah 7:14 was fulfilled in Matthew 1:21. “Reading or listening to Scripture reveals new dimensions of God’s character and his purposes and motivates me to live more fully according to his word. It is like a daily blood transfusion where the Holy Spirit renews and refreshes me.”

“Reading or listening to Scripture reveals new dimensions of God’s character and his purposes and motivates me to live more fully according to his word. It is like a daily blood transfusion where the Holy Spirit renews and refreshes me.”

Still, the reality of Thorn’s work can take its toll, and one glimpse of a chat room transcript can remind staff members of the disturbing darkness beyond the screen. It’s what psychologists call “vicarious trauma,” and the emotional impact can easily tempt them to stop their work. “If you haven’t been taking care of yourself, you hit a rough patch,” Brooke says. “You don’t know what will trigger employees, and I’ve definitely cried on some days.” To keep their work sustainable, Brooke helped Thorn develop a group counseling program and therapy for the employees, a solution that came from her own years of navigating burnout.

Still, the reality of Thorn’s work can take its toll, and one glimpse of a chat room transcript can remind staff members of the disturbing darkness beyond the screen. It’s what psychologists call “vicarious trauma,” and the emotional impact can easily tempt them to stop their work. “If you haven’t been taking care of yourself, you hit a rough patch,” Brooke says. “You don’t know what will trigger employees, and I’ve definitely cried on some days.” To keep their work sustainable, Brooke helped Thorn develop a group counseling program and therapy for the employees, a solution that came from her own years of navigating burnout.

“Reading Scripture is one of the primary ways we resist conforming to this world and instead are transformed by the renewal of our minds (Romans 12:2). Scripture reshapes and reorients our perspectives, attitudes, and values in light of who God is and what God has done for us so that the way we live reflects our truest worship to God.”

“Reading Scripture is one of the primary ways we resist conforming to this world and instead are transformed by the renewal of our minds (Romans 12:2). Scripture reshapes and reorients our perspectives, attitudes, and values in light of who God is and what God has done for us so that the way we live reflects our truest worship to God.” “[The Christian] is concerned with spiritual matters rather than with physical matters. That does not apply to the Muslim. The Muslim is very much concerned with physical matters and he talks more about issues of cleanliness rather than stressing spiritual issues . . . when his body is clean that is when he is noticed by God. It is not like that for a Christian, he says God deals with the heart” [semi-urban male].

“[The Christian] is concerned with spiritual matters rather than with physical matters. That does not apply to the Muslim. The Muslim is very much concerned with physical matters and he talks more about issues of cleanliness rather than stressing spiritual issues . . . when his body is clean that is when he is noticed by God. It is not like that for a Christian, he says God deals with the heart” [semi-urban male].