A Competing Gospel

There is a message of salvation that is proclaimed here and around the world. This salvation message is broadcast as “good news.” This announcement is crafted in numerous ways, using many media. This good news offers us meaning, it engages our imagination, it proclaims a life that is blessed with abundant resources, and it connects us with fellow travelers. This gospel says: “Imagine yourself fulfilled and happy, with your needs met socially, economically, emotionally.”

This is the gospel of consumer capitalism and globalization, a gospel tailored for late-modernity, in which we are all invited to participate. This gospel is personal: “Get in touch with who you really are and form a life around those passions. Imagine yourself in this car, in this career, empowered, loved, influential.” This gospel ignites imaginations, invites participation, and motivates listeners to strive for success.

As with any such invitation, it needs to “come close” so we might be lured to enter. Through TV and movies, internet, magazines, and billboards, everyone can get a picture of this way of life—its wonders and its satisfactions. Even remote villages—perhaps with one electrical outlet—can see the images, hear the metaphors, and re-imagine their own lives reshaped by this gospel. On more than one occasion I have been told by a missionary that a single TV in a village draws an adult crowd after work to watch CNN, then the youth gather to watch MTV. If there is any hope of the people of the world accepting this gospel, this access to their time and imaginations is essential.

This narrative of salvation, this “gospel,” makes promises and seeks commitment: “Leave your father and mother and friends and relocate for your career, for the economy, for an imagined good life. Keep leaving friends and neighborhoods in this pursuit, and keep developing new temporary friendships in ever new locations. Commit your labors and your money to this abundant life. Be mobile in your individual (or nuclear family) decisions in service of the economy or of a career advancement. Use your resources to accumulate the market’s wares and keep the economy going. Be attentive to displays of the good life offered in print and song and images. Follow the teachings of the society—then you will be blessed, you will be participating in the salvation of the world as this way of life is spread to the ends of the earth.”

What I am describing as a parody of the Christian gospel is neither simple greed nor the “health and wealth” gospel that is often and appropriately criticized. I am not suggesting that we should find ways to be a little less “worldly” in our consumption and appearance. I am not primarily concerned with developing habits of simplicity to counter habits of materialism, although that might deserve some attention. Rather I am attempting to describe a narrative, a story, that competes with the narrative of the gospel of God. This competing narrative entails a systemic and powerful network of relationships, activities, institutions, nations, resources, and might that seeks to convert peoples and nations to a way of living. And I believe that many Christians and churches—especially in the so-called first world—have adopted values and practices closer to this parody than to the real thing. Many of our difficulties in understanding the gospel of Jesus Christ can be better understood if we name the forces that compete for our loyalties. Without clarity about these forces, we may believe we are reading scripture or practicing the gospel, but we are tending instead to take this other gospel and use it as the lens through which we see and interpret the gospel of God.

The Gospel of God

What is the gospel of God? How does it relate to its competitors? The Scriptures are full of narratives, images, prophetic words, and teachings that describe and invite:

“Is not this the sort of fast that pleases me: to break unjust fetters, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break all yokes? Is it not sharing your food with the hungry, and sheltering the homeless poor; if you see someone lacking clothes, to clothe him, and not to tum away from your own kin? Then your light will blaze out like the dawn and your wound be quickly healed over. Saving justice will go ahead of you and Yahweh’s glory come behind you” (Isaiah 58:6-8, selected, NJB).

“You are the salt of the earth . . . You are the light of the world. A city built on a hill cannot be hid. Let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father in heaven” (Matt 5:13-16, selected, NRSV).

Each of these passages has its own context and a perspective on what the gospel looks like. I believe that God’s narrative of creation and covenant is constantly interrupted by other salvation stories. So God provides an alternative to the narratives that the world produces, and we have a better ability to understand the gospel when we see it in the context of that which is offered by the world. In each of these contexts, God’s narrative was made visible in competition with the narratives offered by others. We need to understand the context (those narratives offered by the surrounding environment) as we seek to understand and participate in the gospel of God (which is God’s presence and formative initiatives in the narratives of Israel, Jesus, and church).

Isaiah 58 is written in contrast to the years leading up to the Babylonian exile. Several of the prophets tell this story—how God’s people maintained their worship practices, even recited some of God’s promises (often out of context), and otherwise just continued in their normal daily activities of raising families, engaging in labor and trade, and accepting the norms of their national practices. The government, their leaders, created a “mixed narrative” —that is, they lived and taught a certain mix of beliefs, commitments, economics, and religious practices. But Isaiah claimed they were missing God’s story: “You seek your own pleasure, you exploit your workmen, the only purpose of your fasting is to quarrel and squabble” (58:3).

So, as they claimed to be shaped by covenant, as they prayed to God about his promises to preserve them, they failed to enter God’s narrative—God’s story—which is a story of justice, of healing, of working against oppression. Then they were conquered.

Imagine what happens to a people when they face a defeat so humiliating, so tragic, so thorough. This was an experience so overwhelming that they were forced to reject some of their core beliefs. They had heard, “God will always take care of Jerusalem. We are God’s people, God will protect us. God will never let an enemy defeat us.” Then they were not just defeated, they were decimated. Many were killed, much of their land was given to others, their capital was sacked, their temple was destroyed, and hundreds were force-marched across the desert to a new ghetto in Babylon.

In exile, God’s people were not in charge of the governing institutions. They were not the national religious establishment. They had no influence on the morals or social agenda of Babylon. That was the environment where Isaiah understood and proclaimed this vision. In facing the truth about themselves and their context, the gospel of God could be proclaimed: “Your light will blaze out like the dawn and your wound be quickly healed over. Saving justice will go ahead of you and Yahweh’s glory come behind you.”

God’s people, as they embody the grace of God, are to appear as a blazing sunrise. Isaiah provided some very practical, feet-on-the-ground descriptions of what such a people look like. Together, as a covenant people, their embodiment of God’s narrative means that they enter into the work God is doing to counter injustice, to free the oppressed, to feed the hungry, to shelter the homeless. These practices require more than individuals trying to be obedient or heroic. It takes a covenanted people acting over the long haul to build relationships, study the powers, create resources, and link arms to enter gospel work There are appropriate ways for social agencies and governments to create structures and train professionals for these tasks, but I believe Isaiah envisions the people of God, in visible and located groups, living this out day by day.

The passage from Matthew must also be read in light of the political and military climate. Throughout the first century, Roman hegemony was well established in this region. By the time Matthew writes towards the end of the first century, relationships are deteriorating between Jews and Rome, Jews and Christians, and Rome and Christians.

Israel is not an independent nation. It had been absorbed into a global Roman story. Perhaps it is more accurately described as “colonized”: there is a big narrative that has the power of force, the power of a global narrative, the power of economic exchange on its side. That power has a military presence, an economic presence, and a political presence. The believers reading Matthew were living under this colonizing power.

In that context, Jesus—and Matthew after him—image the gospel by describing a well-lighted city. The light of the gospel is not to be hidden—the shining of the city is described specifically as public “good works.” Because there are numerous New Testament references to Isaiah, including references in the Sermon on the Mount, it is not without warrant for one to see connections between the blazing sunrise of Isaiah 58 and the well-lit city of Matthew 5. Once again, the presence and announcement of God’s grace (the gospel) is a narrative of social formation—the creating of a people whose lives attract attention by corporate embodiment of works of mercy, justice, and healing.

This is the context in which Paul’s letters are written. The gospel of God is embodied—conveyed in the congregational practices that are born and sustained by conviction. Such gospel endurance is needed as the environment is seldom helpful. Mediterranean Christians have narratives to chose from—including the Roman narrative of globalization, the narrative of Jewish synagogue leaders, and other local narratives. Which one is God’s? That is to ask, what is the gospel?

These passages raise critical issues: first, are the cultural contexts of exile and colonization helpful in our interpretive work concerning our own context? Secondly, what is the relationship between the gospel and the churches? Is congregational life one option among many, or is the formation of congregations somehow critical to the essence of the gospel?

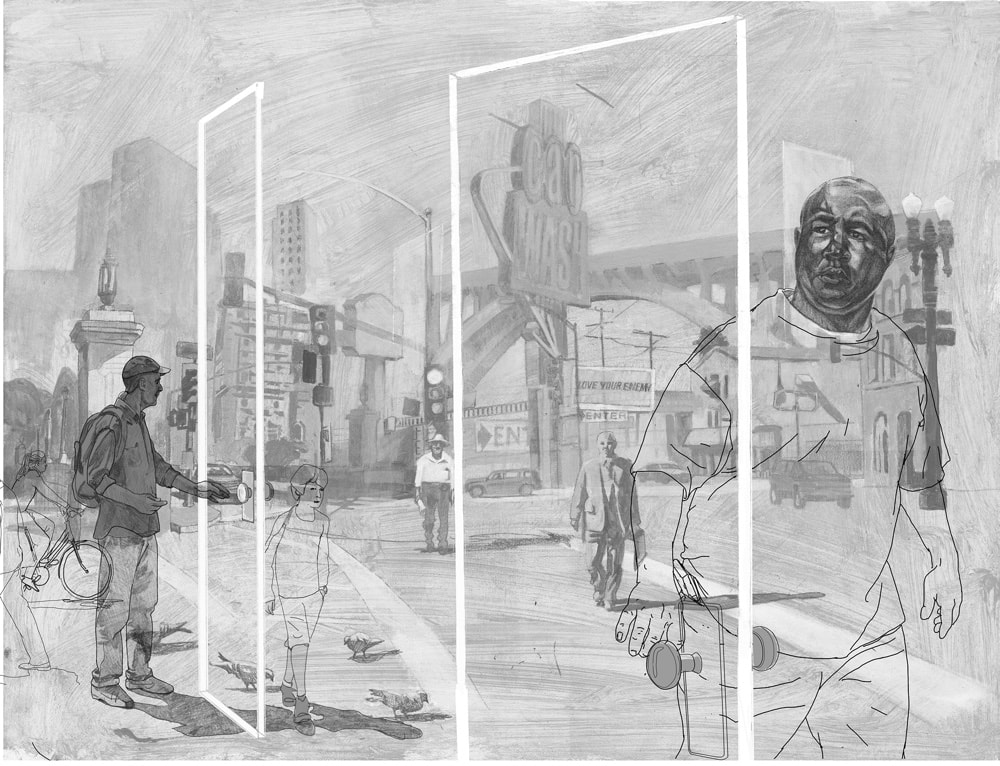

Images of Exile and Colonization

The images of exile (the people of Israel living in Babylon) and colonization (Jews and Christians living under the coercive presence of the Roman Empire) have something in common: some other power has gained dominance. A “big” story seeks to recast the story of God’s people-forming narrative. The passage from Isaiah was written at a time of exile, in anticipation of God forming a faithful, covenant people. Jesus lived—and the Gospel of Matthew was written—at a time of colonization or empire, when the disciples and the early churches, were a tiny minority. Churches today, in attempting to read scripture and embody the gospel need to give attention to how social context (such as exile or colonization) shapes the meaning of a text. Sometimes Christians must deal with oppressive governing structures; sometimes we face threatening powers that take other shapes.

My wife Nina grew up in Texas as the second daughter in a Chinese immigrant family. The family had come to Texas so that her father could fulfill a commitment to work with a friend to establish a small grocery. The preceding years in China had been times of warfare and famine, and this was to be the beginning of a new life in the United States. But as the store was being prepared, their main supplier informed them, “I cannot supply you because many of my other clients have told me they will cancel their orders if I supply you.” Without his supplies, all of their investments of time and money were lost. They struggled for years to create and sustain other means of income.

But that was not the only threat that Nina remembers. In the home, even as a child, she was aware of a darkness that was present because of her grandmother’s practices of traditional Chinese religion. Nina’s father did not allow the traditional altar—even though he did not have other convictions to offer—but the grandmother still continued her rituals. Nina’s sense as a child was that in her home there were spirits that were against her. As a child, she was aware of threats in the world and threats in her home.

In this context, a neighbor invited her to a nearby Baptist church. I believe the denominational tradition made little difference in what she experienced. Nina reports, “In that church I learned that Jesus was a nice white man who loved children. But the stories I heard there had nothing to do with the economic forces that worked against us in the world or the spiritual forces that worked against us in the home.”

The narratives of Israel, the words and works of Jesus, and the Spirit-created churches of the New Testament provide us with a gospel that is sufficient to our salvation, powerful to transform us into something we cannot be on our own. If that gospel is not tangible in our churches, then we are amiss.

Discerning the Gospel of God

There are two late-modern virtues that are important to the gospel of consumerism: individualism and efficiency. Individualism requires that we believe we are acting out of our own choices—so we seek to live our Christian Jives as a set of consumer choices. I do believe that each human is profoundly loved by God, but when such individualism becomes the defining center of the gospel from which other matters are built, then we are misled much as Israel was before the Exile.

Just as expressive individualism is a framework that comes from the Enlightenment as read through the lens of Romanticism, efficiency comes from the Enlightenment through the eras of industrialization and modern management. The promise is that if you take some task (like building a car) and subdivide the operations down to very small parts and activities, you can be efficient. During the last century, as Christians adopted this framework, the inefficiencies of congregations were rejected in favor of fragmentation and specialization. So, “let’s create an Christian organization to evangelize and disciple kids,” or “let’s create an organization to market the gospel to CEOs and disciple them on their own turf.” I do believe there are times for churches to join in some tasks that are larger than a single congregation’s reach—much like Paul’s missional team collected funds for those who were desperately poor in Palestine. And there are good reasons for training and education to be shared among congregations like Priscilla and Aquila’s seminary-on-the-road. These New Testament models are distinctive in that they assume that congregations are at the center of the gospel’s meanings and the gospel’s power.

Here is the core of my concern, focused especially for the American context: Paul and Matthew, reflecting, I believe, the teachings of Jesus, create a strong link between the gospel narrative and congregational life. The light is to be made visible to others. In a national norm akin to life in a food court (e.g. commuter lives, transient careers, temporary commitments, church hopping, etc.) we have adopted narratives antithetical to that gospel narrative.

Have our minds, our theologies, our ecclesiologies been colonized? Some denominations offer helpful, well-crafted public statements, but can they nurture congregations that embody ‘those beliefs? Some agencies deliver food or evangelize kids, but can they form stable, sacrificial, generative congregations so those who are touched can belong to a gospel people?

If we are asking others to repent—to turn from other narratives—what are we asking them to turn to? Do we just ask them to turn to some mix of beliefs as we ourselves work on our own professional specializations and live lives of transience between numerous agencies and churches?

I believe the gospel is an invitation to enter a narrative—a Jewish, eschatological narrative that was definitively revealed in Jesus Christ. We can neither receive nor live the gospel on our own terms; we can only participate on God’s terms. In Jesus, God has redeemed us from other stories; God has come close in Jesus and remains close in the Spirit-formed and Spirit-indwelt “body of Christ” called the church. We receive the gospel narrative by walking in a congregation that is covenanted to practices that make us more vulnerable to the Holy Spirit’s work of forming us. As we study scripture, love each other, love our neighbors, and discern God’s presence and intentions, we are birthed and formed as gospel people. What does it mean for God’s people to look like a blazing sunrise? What does it mean for a group of disciples to be a visible, radiant city on a hill, as they can do the works of the gospel? What is the gospel in Thessalonica, where it is word and power, forming a people of conviction and joy?

In pragmatic, individualized, globalized America, I believe the first vocation of every believer is to be the church, to live and work with others for the continual birthing and converting of people who covenant to embody God’s gospel in a place. Those who enter God’s narrative will be continually reformed by these biblical narratives as the Holy Spirit repeatedly convicts and heals, brings down and lifts up, showing us the way to die in Christ so we might be raised in Christ, so others around us might be drawn to what looks like a blazing sunrise.

+ This article was published in Theology, News & Notes, Spring 2004.

The post Escaping a False Gospel: On Changing Stories appeared first on Fuller Studio.