Christians today often forget that the word translated as “church” in the New Testament, ekklesia, means political assembly. Like the assembly of Israelite authorities from the time of Moses before it, “church” is Scripture’s name for a gathering, political community, with its own law and authority figures. Not surprisingly, when the growth of the Christian movement began to threaten the stability of established Roman society in Asia Minor in the 2nd century AD, the Roman proconsul Pliny issued a decree prohibiting “political associations” (Pliny the Younger, Ep. 10.96) as part of his violent crackdown on Christianity.

Christians today often forget that the word translated as “church” in the New Testament, ekklesia, means political assembly. Like the assembly of Israelite authorities from the time of Moses before it, “church” is Scripture’s name for a gathering, political community, with its own law and authority figures. Not surprisingly, when the growth of the Christian movement began to threaten the stability of established Roman society in Asia Minor in the 2nd century AD, the Roman proconsul Pliny issued a decree prohibiting “political associations” (Pliny the Younger, Ep. 10.96) as part of his violent crackdown on Christianity.

That the church was and is political does not entail the pursuit of violent sovereignty and the imposition of Christian ways on others, however. But it does mean that the Christian church is a public reality, that in the patterns of its life it cannot submit itself to a political authority other than Christ the humble Lord, and that it will always be in a politically influential relationship with the other communities with whom it shares its places.

Because of the ways Christian authorities have historically exercised their political power to oppress those under them, both Christians and others, we find ourselves living today in social arrangements committed to a distinction between “the political” and “the religious.” But as important as restraining Christian overreaching has been, this distinction has fostered a misunderstanding among Christians: that the Christian life is primarily a private matter and only secondarily a public one; that Christianity concerns chiefly the individual and the soul, forming the community and the body only derivatively.

The result of this misunderstanding, this privatization, has been a kind of deafness to the claims of God’s revelation on our political life according to Scripture. With this deafness has come a political life that is not disciplined carefully by that revelation, not discipled by Jesus. Consequently, the Christian presence in political life in the US is often felt as a puritanical crusade whose banner is “the biblical position” on a handful of moral “issues,” positions that influential Christians are prepared to enforce broadly by their numbers and wealth.

Meanwhile, what is Christian about this crusade when it comes to matters of considerable political importance, such as the reconciliation of divided parts of society through reparations, the recourse to military and police violence, the structured system of wealth generation and distribution, and the scale and sustainability of our use of water, land, and animals, is difficult to discern. Christian politics on these matters often seems indistinguishable from the politics of non-Christian powers. In fact, sometimes it’s worse: more arrogant, less patient. Insofar as questionable political commitments on these matters are bundled with “Christian positions” on the signature moral issues, and undergo little if any theological scrutiny themselves, they are supported and embodied by much of the church. Some Christians even find themselves tacit, if not flagrant, spokespersons for politically diseased tendencies on these matters, whether white supremacy, militarism, or predatory commerce, because this bundling has lent these diseases the mystique of moral diligence.

“We place social and political action and advocacy within the framework of the church’s role as caring pastor to society—and within the framework of the teachings of Jesus that ground this vision. At our best, Christians vote, lobby, campaign, meet with political leaders, and become such leaders themselves as a natural outflow of our pastoral concern for the social good under the sovereignty of God who loves all persons. We are alerted to the brokenness, need, and injustice through ministry with people or awareness of their needs, and care for such persons then moves us, in part, toward politics.”

“We place social and political action and advocacy within the framework of the church’s role as caring pastor to society—and within the framework of the teachings of Jesus that ground this vision. At our best, Christians vote, lobby, campaign, meet with political leaders, and become such leaders themselves as a natural outflow of our pastoral concern for the social good under the sovereignty of God who loves all persons. We are alerted to the brokenness, need, and injustice through ministry with people or awareness of their needs, and care for such persons then moves us, in part, toward politics.”

+ Glen Stassen and David Gushee, in their book Kingdom Ethics: Following Jesus in Contemporary Context.

Turbulent political currents in the US do not often bring out the best in people. They expose our vulnerabilities and leave many Christians with the impression that the life of faith should not soil itself with politics. Somehow a squeaky clean Jesus can be peeled from what the New Testament presents quite plainly as a vigorous Jewish man whose way of speaking and otherwise living in public, not least the way he formed community in Israel, got him executed by the imperial occupier of his place and time, charged with the sedition of being king of the Jews. Preferring a tidier, less demanding Jesus, many Christians have withdrawn from any substantive and intentional participation in formal political processes.

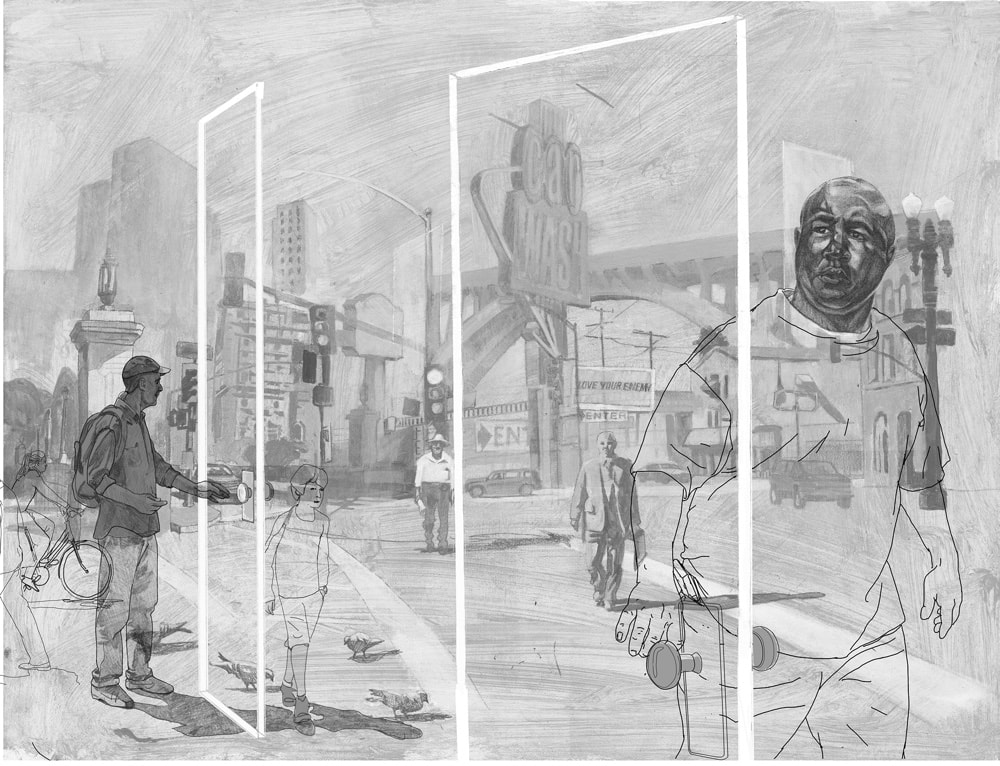

But withdrawal itself is not politically innocent. And other Christians, for whom formal political processes have been key to a minimum of well-being, who have not been able to afford the luxury of waiting on the sidelines, have joined Jesus in the political fray. With a political vision like that of Howard Thurman in Jesus and the Disinherited (1949), they have channelled and embodied the prophetic witness to God’s justice and compassion that we find in the Bible, often at great cost.

Now, as we discern the political roles our churches should play as part of the wider communities of our places, we must certainly not romanticize the political systems of the US. They are not the sole mediator of the political life of Christian communities. Their tendencies to reduce people to voting units or blocs, to bundle political concerns together in incoherent platforms, and to justify unjustifiable sacrifices are symptomatic of the systems’ limits, particularly as the political scale reaches the national and money saturates political processes. The church is called to embody a life-giving political community with or without a healthy political system in its places to give it further expression, and sometimes the church must openly refuse politically established strictures on its political calling. Rather than merely choosing from among the political options, the church must always be involved in generating new options.

But recognizing the limits of US political systems, the church would be unwise to stand aloof from them, particularly where political processes are better scaled to voice the church and its neighbors in their bodily concreteness. These are often more local or regional jurisdictions, where hollow ideology and sloganeering can yield to the more particular concerns of people. Poorly scaled, overextended political structures allow people to “oppose” abortion without doing anything about the social and economic conditions that promote it, or taking into account the particular lives or gender disparity involved. Sweeping political programs can purchase votes for war and corporate greed at the cheap price of a “pro-life” slogan or the rallying cry of “traditional marriage.” But destruction is harder to hide where the distance between rhetoric and results is shorter, where political shortfall is under our noses. Better scaled political structures can convene meaningful processes of organizing, decision-making, and resource development that actually and holistically address community needs and feed neighborliness. It is important for neighbors, not least Christian neighbors, to be able to organize so as to speak to one another as themselves, rather than as estranged and stereotyped members of parties and factions. In Equity, Growth, and Community (2015), Chris Benner and Manuel Pastor have provided hopeful testimony of precisely this kind of healthy political formation around the US.

That the church must not be seduced in national level politics does not mean it should avoid it altogether, but our participation must be judicious. This is especially important when it comes to economic justice, as measuring “economy” nationally often celebrates aggregate gains that hide unacceptable costs to particular places, typically places deprived of political power. Rather than settling for an economic language that measures life in terms of placeless numbers, money, and market values, Christians must promote a scaled language that describes and pursues life in terms of the integrity and sustainability of particular places, including the water, land, and all the human and non-human neighbors of those places, all the relational intricacy that makes those places what they are and what they can become. This is the way the biblical law of Moses addresses the places of the people of God, and Jesus came not to abolish that law but to fulfill it.

The political pursuit of economic justice involves far more than helping people find employment, though not less. It involves the balance of their work and rest, the impact of their work on their place, on their human relationships, and on their personal sense of dignity. In seeking to be a political body of justice in our places, then, to embody and spread neighborly love, the church cannot stand for any of their members or their human and non-human neighbors to be dissolved as “necessary” collateral damage, as justified sacrifices. We proclaim that the final sacrifice for the creation’s full flourishing has been made by the Lord Jesus and that he now lives to empower that flourishing with the resurrection life of the Spirit as we give ourselves to one another. If we care for our neighbors as ourselves this way, we are more apt to develop healthy political and economic relationships with those who live farther away in our globally connected world. We can also grow to exercise sound judgment in our participation in the more formal political processes of our places and the wider society of which we are a part. As communities seeking to embody the justice we proclaim, our political influence may then be felt not as a threat, not as the fragile power of mere numbers or wealth, but as neighborly learners, compelling example, and gentle persuasion.

+ “The Politics of the Church in the World” is a forthcoming essay in Precepts, republished here with their permission.

The post The Politics of the Church in the World appeared first on Fuller Studio.