Leila’s Distress

Recently a Muslim friend, whom I will call Leila, told me bluntly, “I was born in the wrong century.” When I asked why, she said: “Would you feel welcome in the world when there is so much negative talk about Islam and Muslims, and people are so afraid of you? I don’t know where to turn in order to feel that it is okay to be a Muslim and treated like the rest of the world.” I could see deep pain in her eyes as she was talking to me.

![Bubles Illustration by Denise Klitsie]() Until recently, Leila had a good life in France. She and her husband have excellent jobs as doctors. Their children attend reputable schools and have promising careers. Although she was born into a devoted Muslim family who migrated to France, Leila rarely practices her faith and did not disapprove when her children decided to adopt a nonreligious lifestyle. Nevertheless, Leila’s heart is broken when she hears how Muslims are often portrayed as terrorists and Islam considered a threat to civilization. If Leila were the only person with such views, I would not be worried, thinking that she is perhaps too sensitive. But I meet more and more practicing and non-practicing Muslims with similar feelings. If this trend grows, we will see more and more fear, distrust, and hate, which will only escalate existing intractable conflicts.

Until recently, Leila had a good life in France. She and her husband have excellent jobs as doctors. Their children attend reputable schools and have promising careers. Although she was born into a devoted Muslim family who migrated to France, Leila rarely practices her faith and did not disapprove when her children decided to adopt a nonreligious lifestyle. Nevertheless, Leila’s heart is broken when she hears how Muslims are often portrayed as terrorists and Islam considered a threat to civilization. If Leila were the only person with such views, I would not be worried, thinking that she is perhaps too sensitive. But I meet more and more practicing and non-practicing Muslims with similar feelings. If this trend grows, we will see more and more fear, distrust, and hate, which will only escalate existing intractable conflicts.

Indeed, countries that welcomed Muslims in the past are now more reluctant to do so. Muslims who have been living peacefully in those countries for years feel increasingly threatened. Likewise, Christians are increasingly afraid of Muslims, especially since the rise of terrorist attacks, beheadings, and other types of aggressions perpetrated by some in the name of Islam. As Christians, we are standing at a crossroads. We can participate in the current polarization between Muslims and non-Muslims, leading potentially to even greater conflicts than the ones we witness today in Syria and parts of Africa. Or we can join people of good will, like the three Christian scholars of Islam I will describe this article, who invite us to adopt missional practices of hospitality toward Muslims.

At the outset of this article I want to reaffirm that welcoming Muslims does not mean that I water down my faith. I like sharing the gospel with Muslims in the joyful spirit of the resurrection of Christ. In preparation for my talk at the North American InterVarsity Conference in December 2015, I reflected much on this question. I proposed that Christian witness among Muslims today should include “Welcome, Wisdom, and Wonder.”1 I will focus here on “welcome,” because this attitude addresses the first assertion that I heard from Leila: “I do not feel welcomed!”

Muslim-Christian Relations in Times of Terror

Leila admits that today’s tensions are not new. Throughout history, there have been peaceful times but also countless wars and conflicts between Muslims and non-Muslims, including Christians.2 The reasons have been manifold, but often interpreted as theological. Christians and Muslims, who both claim Abraham and Moses3 as their ancestors, disagree on their descriptions of God, salvation, and other key doctrines. But there have been other reasons behind these conflicts, such as the disparity of resources that sometimes exists between religious communities, or claims over territory. Early Muslim empires, for example, conquered land from the Christian Byzantine Empire. Later, during the Crusades and toward the end of the Ottoman Empire, Christians fought to regain control over some of these territories. Today, there are examples of all these types of conflicts. They are often called “religious” because Muslims and Christians, whose worldviews are God-centered, include religious language and ideas to support their actions, but they are often loosely linked with theological controversies and have more to do with economic, political, or social issues.

Thankfully, however, interfaith relations have also included harmonious times throughout history, and even today many contemporary societies have developed models of peaceful interfaith coexistence.4 Freedom of religion is included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In France, Leila has the choice to practice her faith or not. Evangelicals are increasingly engaging in interfaith dialogue without losing their passion for sharing the gospel with Muslims.5 On the Muslim side, the recent Marrakesh Declaration is an important step in protecting the rights of religious minorities in predominantly Muslim majority communities.6 All these examples show that religious pluralism has become the norm in many societies that host different religious communities, although there is still progress to be made—such as, for example, encouraging Muslim societies to provide more protection for Muslim-born followers of Christ, since apostasy is still considered a crime in many Muslim societies.

Why is Leila so distressed, if there is greater freedom of religion? Her anguish is generated by daily global news reports of conflicts involving ISIS, Boko Haram, and other radical Islamic groups. These have drastically altered the dynamics of Muslim-Christian relations. I mentioned earlier that, traditionally, Muslims do not remove God from the public sphere; ISIS moves the rhetoric further. Its entire discourse is saturated with Qur’anic and Hadith passages to justify horrific acts made in the name of Islam, although their war is primarily about territory and influence rather than theology.7 Most Muslims today contest the way ISIS misuses those sacred passages to justify violence, beheadings, and bombings.8 Nevertheless, gradually in the minds of non-Muslims, ISIS becomes the symbol of the “real Islam” and all Muslims become terrorists in waiting! This is what saddens Leila: She is the first to critique the way ISIS uses Qur’anic texts to kill innocent people and does not believe that they represent the majority of Muslims.

There are two reactions Christians can adopt in the face of terrorism. Either they can turn their backs on Muslims out of fear and mistrust (which is legitimate when one faces a real terrorist), or they can seize the opportunity given by this new context of terror to understand Muslims better in general, and to engage with them in the name of Christ. This means that Christians have to ask honest questions: Do I truly know Muslims before I pass judgment? Am I aware of the diversity that exists within Islam? Do I know the theological debates taking place within Islam? Am I ready to address difficult issues such as, for example, recent abuses toward women in Cologne, Germany, allegedly committed by members of Muslim communities?9 Christians and Muslims may be neighbors living next to each other, but that does not mean they deeply know each other. One can live next to a neighbor for a lifetime without truly knowing him or her. Why is it important to get closer to Muslims? Because without a strong bond, humans cannot withstand the kinds of turbulent times we face today. Those who had Muslim friends before the ISIS crisis have reacted very differently than those who did not. These bonds formed with Muslims prior to the conflict affirm that Muslims can be trusted and are not all terrorists in disguise.

Could our current global situation thus offer an opportunity instead of a challenge in Muslim-Christian relations? I see it as an opportunity, and would like to to share some of the ways we can engage with Muslims in a time like this. The way forward is not to live in a place where we retreat from each other. Our times require opening up and conducting a genuine dialogue, not just theological but also societal, looking at how Muslims and Christians can live together on this planet in respectful ways that do not compromise their beliefs. In order to help us practice this kind of hospitality, I share three examples of Christians who decided to turn toward Muslims instead of away from them in times of terror and war. In their presence, Leila would certainly feel welcomed.

Sacred Hospitality

Hospitality was a key concept for Louis Massignon, an eminent French ![Bubbles Illustration by Denise Klitsie]() Catholic Islamicist of the 20th century. Before learning it from the Bible, he personally experienced the lavish hospitality of a Muslim family, who rescued him when he was in captivity in Baghdad, Iraq, in the early 1900s, accused of being a spy in a time of intense conflict between Muslims and Christians in the Middle East. Their extravagant Muslim hospitality was inspired by the desert culture and by precepts from the Qur’an and the Hadith.10 Massignon was deeply moved by this and, later in his life, “sacred hospitality” became a major theme of his engagement with Muslims. He based his reflections on the study of Abraham and the three hosts (Genesis 18:1–10). In Abraham’s time, as in Muhammad’s time in Arabia, there were no institutions and no hotels; hospitality was the responsibility of individuals and families. It was considered a sacred virtue, since the survival of strangers in unfamiliar and hostile places depended solely on the protection of generous hosts. The Genesis passage depicts Abraham sitting at the entrance to his tent on a very hot day. He offered three wayfarers standing nearby water, tree shade, and food as refreshment. Without anticipating it, Abraham ended up hosting messengers of God.

Catholic Islamicist of the 20th century. Before learning it from the Bible, he personally experienced the lavish hospitality of a Muslim family, who rescued him when he was in captivity in Baghdad, Iraq, in the early 1900s, accused of being a spy in a time of intense conflict between Muslims and Christians in the Middle East. Their extravagant Muslim hospitality was inspired by the desert culture and by precepts from the Qur’an and the Hadith.10 Massignon was deeply moved by this and, later in his life, “sacred hospitality” became a major theme of his engagement with Muslims. He based his reflections on the study of Abraham and the three hosts (Genesis 18:1–10). In Abraham’s time, as in Muhammad’s time in Arabia, there were no institutions and no hotels; hospitality was the responsibility of individuals and families. It was considered a sacred virtue, since the survival of strangers in unfamiliar and hostile places depended solely on the protection of generous hosts. The Genesis passage depicts Abraham sitting at the entrance to his tent on a very hot day. He offered three wayfarers standing nearby water, tree shade, and food as refreshment. Without anticipating it, Abraham ended up hosting messengers of God.

Massignon developed this theme of hospitality to stimulate Christians to engage with Muslims. To Massignon, sacred hospitality was shaped by the example of God who is “at once Guest, Host, and Home”11—reflections that inspired many Islamicists to use this model of engagement with Muslims.12 He practiced this model of hospitality not just in times of peace but also during the French-Algerian war in the 1960s, showing that sacred hospitality is also relevant when there are risks involved, as enacted by the Muslim family who rescued him in Iraq. This led Massignon to very practical actions, such as helping peaceful Algerian demonstrators who were arrested in the streets of Paris on October 17, 1961, by trying to “recover bodies [of those] discarded in the River Seine to provide proper Islamic burials. His efforts elicited physical attacks at speaking engagements and criticism by embarrassed friends and family.”13 Massignon’s love for the Algerians in times of war deeply touched the heart of Leila when I told her that story.

Inverted Perspective

Miroslav Volf, professor of theology at Yale Divinity School, provides a second model for hospitality in times of terror. As a Croatian Protestant he experienced firsthand the conflict between Muslims and Christians in the Balkans.14 He has also wrestled with the question of reconciliation after 9/11.15 In a chapter on “Living with the ‘Other,’” Volf explains what he means by “inverted perspective.”16 He writes, “if we consider other people like ‘other’, namely ‘not so good in some regard as I am myself,’ then, I am also an ‘other’ to this person.” That is certainly what Leila is feeling. Once she was ‘the other’ in a negative way to French people, the French became ‘the other’ to her and she felt a deep disconnect. How would she not feel undesirably “other” when the daily news reports horrific acts coming from people who claim they are Muslims, or when a Google search for images of Muslims essentially reveals horrific faces, or when the fear of Muslims becomes a motto to win elections? Psychologists know that negative memories are easier to remember than happy ones.17 Who remembers the news of a happy Muslim family versus the bombing of a school by Muslims?

Volf invites us to understand the “reciprocity involved in the relation of otherness” so that we also better understand what others think of us. After the terrorist attacks in Paris on November 13, 2015, I recalled the people who came through my apartment in Paris during my many years of ministry among Muslims there. Hundreds of young second-generation North Africans attended our Bible studies. Some were extremely distressed by that feeling of derogatory “otherness.” Several became followers of Jesus, while others remained Muslim or became faithless. I wonder if the feeling of “otherness” is not one of the feelings that ISIS plays on to attract some into perpetrating the horrific terrorist acts committed in Paris. Could we, as Christians, practice inverted perspective to help others not choose this way but instead feel deeply connected to the country in which they live?

Volf tells us that inverted perspective invites us to “see others through their own eyes.” This to me involves listening and even more: the other must feel that you have truly heard him or her. In conversations with Leila this would mean hearing not just the positive things she has to say about non-Muslims, but also the pain she feels and her feelings of rejection, without automatically reacting in defensiveness. Volf’s “inverted perspective” also invites us to “see ourselves through the eyes of others.” Do we ask Muslims how they see us? Of course, they may not express these feelings right away, but instead of systematically rejecting their critiques, can we take time to listen to their grievances as we hope they will listen to ours?

What I like about Volf’s approach is that he does not ask people to avoid the tough questions; rather, he knows that they need a safe place for holding those conversations. He calls this “embrace.”18 Without a safe and welcoming context, communication will not succeed. Unfortunately, in our current times Muslims and Christians often start with arguing before listening to each other. I read Volf’s book many years ago but picked it up again recently because I believe it is so relevant for today’s context. “Embrace” is a form of hospitality. It does not ignore challenges. It welcomes hospitality rules that provide safety not for one but all communities involved, protects the human rights of all individuals, looks at all the consequences (short- and long-term) of welcoming new communities, and pays special attention to the poor and the needy. This hospitality is practiced with the mind of Christ.19

The Gospel of Reconciliation

In an article on the gospel of reconciliation within the wrath of nations, missiologist David W. Shenk discusses peacemaking in a conflict-ridden context in Indonesia between Muslim and Christian communities.20 He explains how a Christian pastor leading a reconciliation movement in Indonesia paid a visit to a Muslim leader. Shenk writes, “The commander greeted him gruffly: ‘You are a Christian and an infidel, and therefore I can kill you!’ Unfazed, the pastor returned again and again to the commander’s center to drink tea and converse.”21 Later the pastor invited this leader to help in the post-tsunami reconstruction work of Banda Aceh. As these two leaders, Muslim and Christian, worked together, shared the same room, and ate together, they became friends. Shenk concludes this article by saying, “One evening around the evening meal, the commander began to weep. He said, ‘When I think of what we have done to you, and how you reciprocate with love, my heart has melted within me!’ He confided to the pastor, ‘I have discovered that you Christians are good infidels.’”22

I report this story to remind us that in times of war and terror, there have been Christians who God has used as peacemakers and witnesses of the gospel of reconciliation. I will never forget the example of the seven Cistercian monks of the Abbey of Tibhirine in Algeria, who were murdered in 1996 because they wanted to stay with their Algerian friends during a brutal civil war in which terrorism claimed the lives of over 200,000 Algerian civilians. Hospitality and welcome can pose aggravated risks in wartime. I would not recommend to anyone that he or she stay in a context of terror to be a witness, but some choose to do so because they feel God’s calling to share the struggles of innocent populations who cannot flee war.

The devastating consequence of terrorism, beyond of course the killing of innocent people, is that it destroys the practice of hospitality. We are afraid to invite the “other” or to be guests of the “other.” We need to acknowledge this challenge in order to be wise in our practice of hospitality. Welcome is concerned about safety. In any culture where hospitality is valued, there are rules to make the practice of hospitality sustainable long term. Furthermore, hospitality must sometimes be practiced from a position of weakness and not of power. The Cistercian monks of Tibhirine made the choice to be weak and to become guests of those who suffered and were in danger. Not everyone will be led to experience hospitality in such dangerous contexts, but the lessons of hospitality from a position of weakness are an integral part of mission.23 Our greatest model is Jesus, who lived in times of interfaith and interethnic conflict. He was both a host and a guest of those who were despised. He entered the house of Zacchaeus and accepted water from a Samaritan woman. They were considered foreign, heretic, immoral by people in their local community. Jesus welcomed them not as a host but as a guest, just as he would certainly become a guest to Leila and ask for her hospitality. And just as he became a guest in the lives of all of us who now call him Lord.

Conclusion

Many have this question on their minds: Should Christians support a temporary moratorium on hospitality during times of terrorism? I hope my article shows that they should not. Hospitality and welcome are Christian practices, as they are for Muslims. Let’s be hospitable in the name of Christ, without ignoring the unique challenges that times of terror bring. Let’s design practices that are not based on emotional responses only, but that shape a long-term future in which religious communities can peacefully live together because they know and respect each other deeply. I hope that the three models provided here will be useful resources for those who want to exercise this kind of interfaith hospitality. Although my article starts with the painful feelings of Leila, I trust that she will meet more and more people who will understand and practice sacred hospitality, act out of an inverted perspective, and live out the gospel of reconciliation.

![Hospitality Illustration by Denise Klitsie]()

ENDNOTES

1. “Welcome, Wisdom, and Wonder,” presentation at InterVarsity’s Urbana youth mission conference, December 29, 2015, available at https://vimeo.com/150282939 or https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fNd0auxPdis.

2. In his book, A History of Christian-Muslim Relations (Edinburgh University Press, 2000), Hugh Goddard, professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Edinburgh, retraces major events characterizing the encounter between Christians and Muslims throughout history with its ups and downs.

3. See, for example, Qur’an 3:84, which reads, “We believe in God, and that which has been sent down on us, and sent down on Abraham and Ishmael, Isaac and Jacob, and the Tribes, and in that which was given to Moses and Jesus, and the Prophets, of their Lord; we make no division between any of them, and to Him we surrender” (Arberry’s translation).

4. See Goddard, History of Christian-Muslim Relations.

5. See, for example, Mohammed Abu-Nimer and David Augsburger, eds., Peace-Building by, between, and beyond Muslims and Evangelical Christians (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009); or the Fall 2015 issue of Evangelical Interfaith Dialogue, ed. Cory Willson and Matthew Krabill, Fuller Theological Seminary, at http://cms.fuller.edu/EIFD/issues/Fall_2015/Fall_2015.aspx.

6. Marrakesh Declaration, January 2016, available at http://www.marrakeshdeclaration.org. Read J. Dudley Woodberry’s comments on this declaration at http://fuller.edu/Blogs/Global-Reflections/Posts/A-Christian-Response-to-a-Muslim-Declaration-of-Rights-for-Religious-Minorities/.

7. Read the analyses of several Christian missiologists regarding ISIS and other radical groups on the following websites: https://imeslebanon.wordpress.com/2014/12/04/how-isis-should-shape-our-view-of-the-church-and-its-mission-globally/; https://imeslebanon.wordpress.com/2015/02/20/beating-back-isis/; https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2015-03/the-challenge-of-radical-islam.

8. See, for example, Asma Afsaruddin, “Twenty-First Century Islam: A Lived, Dynamic, and Nurturing Religion,” in The Future of Religion: Traditions in Transition, ed. Kathleen Mulhern (Englewood, CO: Patheos Press, 2012), Kindle ed. loc. 2941-2992; also see the Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi, the self-proclaimed leader of ISIS, which at this date includes signatures of 126 Muslim leaders challenging Al-Baghdadi’s interpretations of the Qur’an and Hadith, at http://www.lettertobaghdadi.com.

9. Melissa Eddy, “Reports of Attacks on Women in Germany Heighten Tension Over Migrants,” New York Times Online, January 5, 2016, at http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/06/world/europe/coordinated-attacks-on-women-in-cologne-were-unprecedented-germany-says.html?_r=0.

10. See the Qur’anic story of Abraham who lavishly welcomes the guests who announce to him the birth of a son (Qur’an 51:24-28); see also the following hadith from Sahih Bukhari (book 1, chapter 19, hadith 75) at http://sunnah.com/muslim/1/80: “He who believes in Allah and the Last Day should either utter good words or better keep silence; and he who believes in Allah and the Last Day should treat his neighbor with kindness and he who believes in Allah and the Last Day should show hospitality to his guest.”

11. Louis Massignon, L’Hospitalité Sacrée [Sacred Hospitality] (Paris: Nouvelle Cité, 1987), 121.

12. Silas Webster Allard, “In the Shade of the Oaks of Mamre: Hospitality as a Framework for Political Engagement between Christians and Muslims,” Political Theology, August 1, 2012.

13. Gordon Oyer, “Louis Massignon and the Seeds of Thomas Merton’s ‘Monastic Protest,’” at http://gordonoyer.weebly.com/uploads/2/7/4/8/27486123/oyer_84-96-1.pdf.

14. Miroslav Volf, Exclusion & Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1996).

15. Miroslav Volf, “To Embrace the Enemy: Is Reconciliation Possible in the Wake of Such Evil?” Christianity Today, September 2001, at http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2001/septemberweb-only/9-17-53.0.html.

16. J. Dudley Woodberry, Osman Zümrüt, and Mustafa Köylü, “Living with the ‘Other,’” in Muslim and Christian Reflections on Peace: Divine and Human Dimensions (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2005), 3–22.

17. Elizabeth A. Kensinger, “Negative Emotion Enhance Memory Accuracy: Behavioral and Neuroimaging Evidence,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 16, no. 4 (2007): 213–218.

18. For the concept of “embrace,” see Volf, Exclusion & Embrace.

19. Philippians 2:5–16.

20. David W. Shenk, “The Gospel of Reconciliation Within the Wrath of Nations,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 32, no. 1 (2008): 3–9.

21. Ibid., 3.

22. Ibid.

23. See, for example, the article by Swiss missiologist Tobias Brandner, “Hosts and Guests: Hospitality as an Emerging Paradigm in Mission,” International Review of Mission 102, no. 1 (April 2013): 94-102.

The post A Moratorium on Hospitality? appeared first on Fuller Studio.

these disturbing curses? Should we follow the lead of the lectionaries and skip them? Or should we play them up?”

these disturbing curses? Should we follow the lead of the lectionaries and skip them? Or should we play them up?”

Joy Moore: While we’ve come together this evening to talk about unjust legacies, and we’ve come together to talk about the difficult conversation of race, privilege, and justice, I want to remind you that we don’t come here as experts talking at you. We come together as brothers and sisters in Christ. Our gathering together is the expectation that we come knowing that if we can name sin by the power of the Holy Spirit, and we can talk honestly about who we are and where we are, that together we can make a difference in the world. That’s the task of the church.

Joy Moore: While we’ve come together this evening to talk about unjust legacies, and we’ve come together to talk about the difficult conversation of race, privilege, and justice, I want to remind you that we don’t come here as experts talking at you. We come together as brothers and sisters in Christ. Our gathering together is the expectation that we come knowing that if we can name sin by the power of the Holy Spirit, and we can talk honestly about who we are and where we are, that together we can make a difference in the world. That’s the task of the church.

“For too long we’ve become complicit in having monocultural, one-language congregations. If the church means to only gather with people like me, then it’s not church. It’s called a social club, and we’re not perpetuating the gospel

“For too long we’ve become complicit in having monocultural, one-language congregations. If the church means to only gather with people like me, then it’s not church. It’s called a social club, and we’re not perpetuating the gospel “Could it be that we are missing out on the 21st century transfiguration of Jesus because we are too comfortable with the Jesus of our failed imaginations? Like the disciples, we are weighed down with sleep. In the words of Martin Luther King Jr., could it be that what weighs us down in our sleep is that we are too hypnotized from carrying the burdens of racism, materialism, capitalistic exploitation, and the over-militarizing of this world? But when you and I know what’s keeping us asleep, we can begin to make different choices. If we are asleep, we may miss seeing Jesus.”

“Could it be that we are missing out on the 21st century transfiguration of Jesus because we are too comfortable with the Jesus of our failed imaginations? Like the disciples, we are weighed down with sleep. In the words of Martin Luther King Jr., could it be that what weighs us down in our sleep is that we are too hypnotized from carrying the burdens of racism, materialism, capitalistic exploitation, and the over-militarizing of this world? But when you and I know what’s keeping us asleep, we can begin to make different choices. If we are asleep, we may miss seeing Jesus.”

“When you actually encounter people of other faiths rather than talk about encountering people of other faiths, a lot of the usual debates begin to drop away. It’s easy to demonize other groups without actually encountering those groups. As soon as you start encountering them, the caricatures are shattered and we find they’re humans with the same sorts of issues as us. Often they have pertinent questions to ask us of our faith that challenge us

“When you actually encounter people of other faiths rather than talk about encountering people of other faiths, a lot of the usual debates begin to drop away. It’s easy to demonize other groups without actually encountering those groups. As soon as you start encountering them, the caricatures are shattered and we find they’re humans with the same sorts of issues as us. Often they have pertinent questions to ask us of our faith that challenge us “One of the most profound marks of justice is the naming of the truth about the victim, the injustice, the perpetrator, the law, the consequences. Of course, discerning the right names about such things can be difficult. But more often the only real difficulty is the lack of will and resources to do so. Power is one the side of the misnamers. . . . Justice renames the forgotten as the remembered, the widow as the loved, and the oppressed as the treasured. Naming gives life misnaming has taken away. . . . When we truly name one another, we are reflecting the God we worship.”

“One of the most profound marks of justice is the naming of the truth about the victim, the injustice, the perpetrator, the law, the consequences. Of course, discerning the right names about such things can be difficult. But more often the only real difficulty is the lack of will and resources to do so. Power is one the side of the misnamers. . . . Justice renames the forgotten as the remembered, the widow as the loved, and the oppressed as the treasured. Naming gives life misnaming has taken away. . . . When we truly name one another, we are reflecting the God we worship.”

“The problem among the rulers of Jesus’ people is their tendency to maintain authority through token acts of justice and law observance which conceal the widespread injustice in which they are complicit, thus neglecting the justice of love that the Law enjoins. They are so addicted to those patterns of injustice and to the influence and resources they gain from them that they find themselves seeking to destroy the One who is exposing them

“The problem among the rulers of Jesus’ people is their tendency to maintain authority through token acts of justice and law observance which conceal the widespread injustice in which they are complicit, thus neglecting the justice of love that the Law enjoins. They are so addicted to those patterns of injustice and to the influence and resources they gain from them that they find themselves seeking to destroy the One who is exposing them “We have a mandate to love God and to love our neighbor and care for the stranger. I think we have to continue reminding the church and educating the church through intercessory prayer and Christian activism and a lot of patience. We live in a culture that’s afraid of the stranger, and we live in a time right now where it’s ‘us versus them.’ It is at this moment that the church has to bear witness to who we are and how we’re different from the rest of the world in how we see the least of these and the marginalized.”

“We have a mandate to love God and to love our neighbor and care for the stranger. I think we have to continue reminding the church and educating the church through intercessory prayer and Christian activism and a lot of patience. We live in a culture that’s afraid of the stranger, and we live in a time right now where it’s ‘us versus them.’ It is at this moment that the church has to bear witness to who we are and how we’re different from the rest of the world in how we see the least of these and the marginalized.” “One of the American myths is that we’re all individuals and we all make it on our own, and that’s why it’s so hard to even have a conversation on privilege because we can’t even acknowledge that as a group, as a socioeconomic class, as people that have certain common characteristics, some benefit and some do not. . . . I want us to think about privilege as the thing that we have but don’t think about and a thing that frames reality.”

“One of the American myths is that we’re all individuals and we all make it on our own, and that’s why it’s so hard to even have a conversation on privilege because we can’t even acknowledge that as a group, as a socioeconomic class, as people that have certain common characteristics, some benefit and some do not. . . . I want us to think about privilege as the thing that we have but don’t think about and a thing that frames reality.”

Until recently, Leila had a good life in France. She and her husband have excellent jobs as doctors. Their children attend reputable schools and have promising careers. Although she was born into a devoted Muslim family who migrated to France, Leila rarely practices her faith and did not disapprove when her children decided to adopt a nonreligious lifestyle. Nevertheless, Leila’s heart is broken when she hears how Muslims are often portrayed as terrorists and Islam considered a threat to civilization. If Leila were the only person with such views, I would not be worried, thinking that she is perhaps too sensitive. But I meet more and more practicing and non-practicing Muslims with similar feelings. If this trend grows, we will see more and more fear, distrust, and hate, which will only escalate existing intractable conflicts.

Until recently, Leila had a good life in France. She and her husband have excellent jobs as doctors. Their children attend reputable schools and have promising careers. Although she was born into a devoted Muslim family who migrated to France, Leila rarely practices her faith and did not disapprove when her children decided to adopt a nonreligious lifestyle. Nevertheless, Leila’s heart is broken when she hears how Muslims are often portrayed as terrorists and Islam considered a threat to civilization. If Leila were the only person with such views, I would not be worried, thinking that she is perhaps too sensitive. But I meet more and more practicing and non-practicing Muslims with similar feelings. If this trend grows, we will see more and more fear, distrust, and hate, which will only escalate existing intractable conflicts. Catholic Islamicist of the 20th century. Before learning it from the Bible, he personally experienced the lavish hospitality of a Muslim family, who rescued him when he was in captivity in Baghdad, Iraq, in the early 1900s, accused of being a spy in a time of intense conflict between Muslims and Christians in the Middle East. Their extravagant Muslim hospitality was inspired by the desert culture and by precepts from the Qur’an and the Hadith.10 Massignon was deeply moved by this and, later in his life, “sacred hospitality” became a major theme of his engagement with Muslims. He based his reflections on the study of Abraham and the three hosts (Genesis 18:1–10). In Abraham’s time, as in Muhammad’s time in Arabia, there were no institutions and no hotels; hospitality was the responsibility of individuals and families. It was considered a sacred virtue, since the survival of strangers in unfamiliar and hostile places depended solely on the protection of generous hosts. The Genesis passage depicts Abraham sitting at the entrance to his tent on a very hot day. He offered three wayfarers standing nearby water, tree shade, and food as refreshment. Without anticipating it, Abraham ended up hosting messengers of God.

Catholic Islamicist of the 20th century. Before learning it from the Bible, he personally experienced the lavish hospitality of a Muslim family, who rescued him when he was in captivity in Baghdad, Iraq, in the early 1900s, accused of being a spy in a time of intense conflict between Muslims and Christians in the Middle East. Their extravagant Muslim hospitality was inspired by the desert culture and by precepts from the Qur’an and the Hadith.10 Massignon was deeply moved by this and, later in his life, “sacred hospitality” became a major theme of his engagement with Muslims. He based his reflections on the study of Abraham and the three hosts (Genesis 18:1–10). In Abraham’s time, as in Muhammad’s time in Arabia, there were no institutions and no hotels; hospitality was the responsibility of individuals and families. It was considered a sacred virtue, since the survival of strangers in unfamiliar and hostile places depended solely on the protection of generous hosts. The Genesis passage depicts Abraham sitting at the entrance to his tent on a very hot day. He offered three wayfarers standing nearby water, tree shade, and food as refreshment. Without anticipating it, Abraham ended up hosting messengers of God.

+

+

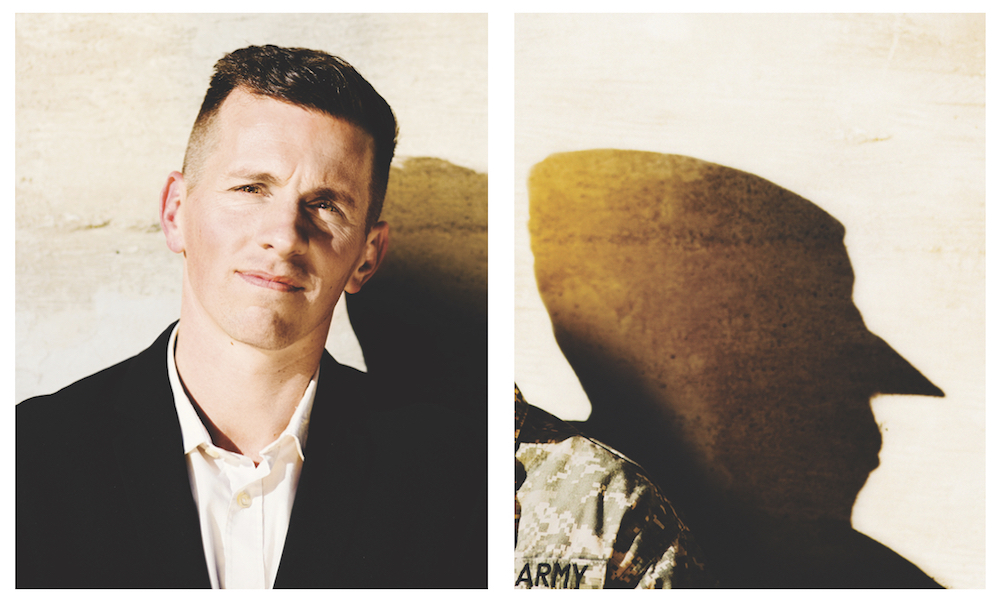

As he does the work of helping to make Los Angeles a kinder place to its veterans, Nate looks to two Fuller professors who were particularly formative. The late ethics professor Glen Stassen modeled an approach that didn’t shy away from seemingly intractable challenges. “He tried to take on the world,” Nate recalls. “He was always asking hard questions

As he does the work of helping to make Los Angeles a kinder place to its veterans, Nate looks to two Fuller professors who were particularly formative. The late ethics professor Glen Stassen modeled an approach that didn’t shy away from seemingly intractable challenges. “He tried to take on the world,” Nate recalls. “He was always asking hard questions

“What if we rewarded a demonstrated ability to think well: to detect our own informational blind spots, generate and evaluate various viewpoints, and recognize what sorts of conclusions one can and cannot safely draw from evidence? . . . Intellectual progress is made when we find the weaknesses and strengths in each others’ positions and think of ourselves as part of a greater collaboration towards the pursuit of truth and insight, where ideas are not regarded as our possessions or a means for self-promotion.”

“What if we rewarded a demonstrated ability to think well: to detect our own informational blind spots, generate and evaluate various viewpoints, and recognize what sorts of conclusions one can and cannot safely draw from evidence? . . . Intellectual progress is made when we find the weaknesses and strengths in each others’ positions and think of ourselves as part of a greater collaboration towards the pursuit of truth and insight, where ideas are not regarded as our possessions or a means for self-promotion.” HUMILITY AND PREACHING

HUMILITY AND PREACHING